Keeping rural Australians out of hospital

Dr Kristen Glenister and Tessa Archbold

If you need urgent medical attention in a regional or rural area in Australia, you may find that you’ll end up in an urgent care centre staffed by nurses. If you do need a doctor, one can be called in, but the doctor will likely charge you — and that can end up costing quite a lot.

In a small, rural town in northern Victoria, the urgent care centre advises patients that they will incur a fee if the doctor needs to attend.

This is on top of any pathology, medical imaging and transport fees.

Often the total amount is unknown at the time a patient comes in which is a confronting reality for anyone requiring urgent care.

If you are on a low income, which many people are in regional and rural areas, these fees could be enough to make you think twice about just how urgent your medical issue is. And the danger then is that by not seeking care when it’s needed, your problem could just get worse.

This can end up being not only bad for people’s health but could put a greater burden on the entire health system because by not treating a problem early patients can end up in hospital later.

This is a type of ‘preventable hospitalisation’ and it’s a major problem for communities right across regional and rural Victoria.

But addressing the issue is complex.

Even with Australia’s Medicare system, the cost is a problem for low-income earners, but there also needs to be work done on improving people’s relationships with the healthcare system and ensuring continuity of care.

In our latest research, we have tried to better understand some of these complexities through detailed interviews with patients who were recently hospitalised for a long-term ‘chronic’ health condition as well as conversations with the health professionals involved in their care.

Our study was based in a regional Victorian town that was experiencing higher-than-state average preventable hospitalisations.

The term ‘potentially preventable hospitalisation’ is an umbrella one that describes hospital stays that could have been avoided with optimal access to primary health care, including affordable GP appointments when and where they are needed.

The use of the word ‘affordable’ may seem curious to Australians who are used to bulk-billed GP appointments, but bulk-billing rates in Australia are at their lowest in regional areas.

In the town where this study was set, bulk-billing rates are even lower than in other regional areas and there are no bulk-billing-only clinics.

Across Australia, bulk billing is under increasing strain due to rising clinic business costs and stagnated, inadequate Medicare rebates. Out-of-pocket expenses for visiting the GP can be high, particularly for people with ongoing health conditions.

One health professional we spoke to said:

“They [patients] might be looking at $AU80 for a 15-minute appointment and they only get $AU35 back, so if you’re expected to see your GP every week or fortnight, well you can see how people slip through the cracks”.

The impact of these costs was highlighted by one patient:

“I’m broke, I can’t get a job. I’m living off [Centrelink] New Start. It’s not enough. I have not enough food, I’m getting food vouchers to survive. I have to count potatoes. They [health professionals] don’t get it. They don’t live like that.”

GP appointments also need to be accessed quickly when people become unwell, which can be hampered by long waiting times and GP shortages which have been long-standing issues in rural areas.

If patients can’t see a GP in time, or the GP didn’t respond when a patient said their condition was deteriorating — what would have been a simple issue could suddenly become complex.

“I actually had to get the MICA [Mobile Intensive Care Ambulance] paramedic down to me because that’s how bad I was. It might have been a two-day stay instead of nine days, if the doctor listened”.

Our study found that issues within general practice, including cost, were not the only factors that contribute to preventable hospitalisation.

The patients and health professionals we interviewed also told us that people who lived alone were often at greater risk.

These are people who may not have someone close that recognises when their health is deteriorating and advises them to seek help or to advocate for them when they are unable to advocate for themselves.

“There is no one there to tell you to go to the doctor… so maybe you missed that opportunity where it can be fixed quickly, then it’s panic stations and I have to go to the hospital because there’s no one around to look after me.”

Conversely, good relationships between patients and trusted health professionals assisted patients in managing their health.

In some regional areas, including the town our study focused on, local GPs also provide care at the hospital, contributing to a continuum of care which often meant that GPs knew patients and their unique circumstances very well.

But not having a person dedicated to their discharge planning at the hospital also means that some patients may go home from hospital without being connected to beneficial local services — like home help or Meals On Wheels — or without understanding why they had been in hospital or properly informed of any changes to their medications.

So how do we tackle these issues and help to reduce preventable hospitalisations in rural communities?

Some solutions may lie outside of the health system — for example, addressing socioeconomic disadvantage or out-of-pocket healthcare costs which require system-level change.

However, other solutions are more straightforward like connecting patients with beneficial local health and social services and providing patients with clear and useful information about their condition as well as advice on how to look after their health.

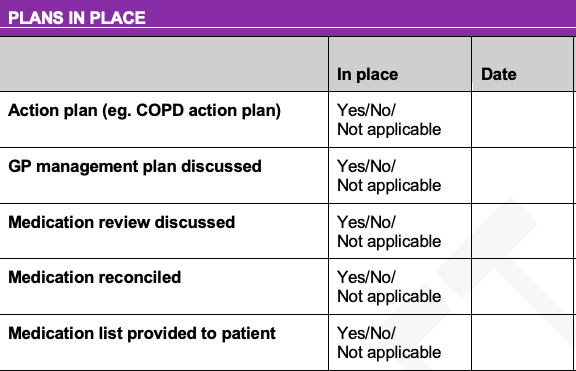

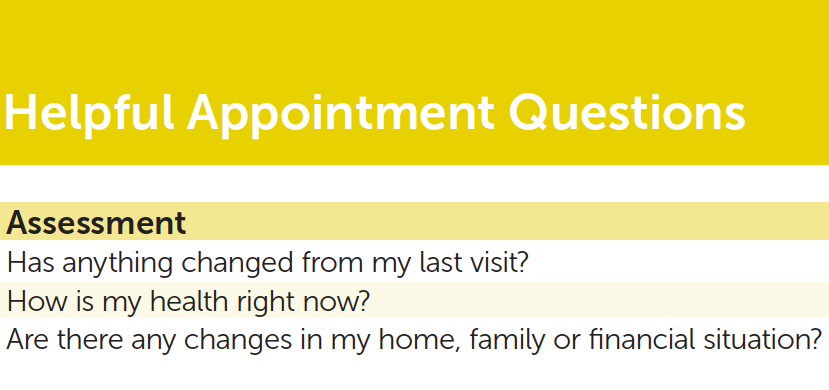

A simple discharge checklist was developed as a result of our study, along with a booklet patients can take home with them.

Talking to both patients and health professionals is crucial in understanding the complexity of preventable hospitalisations and finding local solutions.

By highlighting these issues as well as other rural health inequities, we can ensure measures are in place to improve access to care and health outcomes for all people in Australia, regardless of where they live.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Originally published here.

Remote laundries target preventable disease in NT communities

A new community laundry has launched in Borroloola, part of a program seeking to curb preventable...

Eye care partnership looks to support First Nations optometrists

A new scholarship initiative will support Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander optometrists...

A Day in the Life of a mobile optometrist

Linda Nguyen is the owner and founder of mobile optometrist practice Care Optometry and was a...

![[New Zealand] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89856/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)

![[Australia] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89855/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)