Back pain: active approaches, not medication, more effective

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (the Commission) is advocating a shift towards active approaches to support Australians with low back pain, with the release of a new clinical care standard.

The new Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard provides a road map for healthcare practitioners to help patients manage low back pain episodes early and reduce their chance of ongoing problems.

The use of imaging tests, bed rest, pain medicines and surgery is now accepted as having a limited role in managing most people with low back pain. Current evidence shows an active approach is more effective and less risky for patients.

The new standard recommendations include self-management and physical activity, addressing psychological barriers to recovery such as thoughts and emotions about pain, as well as tackling social obstacles, including work and home stress.

Active approach vs medical interventions

Clinical lead for the new standard Associate Professor Liz Marles, Clinical Director at the Commission and a general practitioner, said the standard marks a leap forward in effective care for low back pain patients, who may be treated across different healthcare disciplines and often receive conflicting advice.

“The Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard describes how active self-managed strategies that educate people about their pain and how to remain physically active and working are most effective to restore health,” Marles said.

“Contrary to past schools of thought, for most cases of low back pain, we know that passive approaches such as bed rest and medication can lead to worsening disability. Also, if pain medicines are prescribed, they should be used to enable physical activities to help people recover, rather than eliminate pain.”

For people with a new episode of low back pain, a thorough initial assessment is vital and should screen for serious underlying causes, such as cancer, infections or nerve compression.

Although Marles emphasised that the risk of a serious cause was very low (1–5%) and usually identified through history and physical examination, cautioning that otherwise investigations can sometimes paradoxically delay recovery.

“Referring low back pain patients for imaging who don’t have any signs of a serious condition may lead to unnecessary concern or wrong care. Common findings on back scans include disc degeneration, bulges and arthritis; yet these are often found on scans of people who do not have back pain — so these findings can be unhelpful and misleading,” she said.

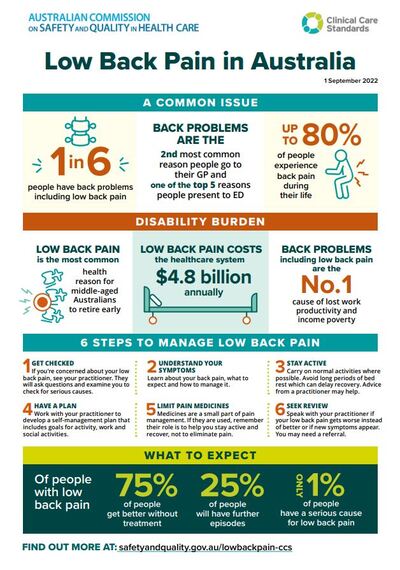

“The good news is that most people who have a single episode of low back pain 75% of patientsi — will improve rapidly and their pain will resolve within six weeks,” Marles said.

For some people, however, she said the condition can put lives on hold, affecting a person’s ability to work and engage in physical and social activities, as well as their mental health.

“With this new standard, we are aiming to break the cycle and prevent a new episode of low back pain becoming a chronic problem for many Australians.”

Overcoming fear

Professor Peter O’Sullivan, Professor of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy, Curtin University, is an advocate of tailoring care to the needs of patients who experience low back pain. He has joined the call for consistency in how early back pain is managed across professions.

“Low back pain is one of the most feared health conditions. We have a societal problem around the fundamental beliefs about back pain. There are many cases of fear-induced over-treatment of patients, which can make their condition worse,” he said.

“As practitioners, we need to understand what is going on with each patient and help them with a specific recovery plan. The evidence shows, and the standard reaffirms, that regular and graduated movement and activity are central to a better outcome for many people with an acute low back pain episode.”

O’Sullivan said low back pain can cause significant discomfort and suffering for some people, but it was important to reassure patients that they have a good chance of recovery.

“With an aging population, growing obesity rates and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, implementing the new clinical care standard is our best chance to remove barriers to good patient outcomes. The recommendations aim to reduce investigations and treatments that may be ineffective or harmful.”

O’Sullivan said it was important for clinicians to educate their patients and provide a clear recovery plan with self-care options that build people’s confidence in their back and put them in charge of their health, through knowledge, exercise, physical activity and work.

“Patients with low back pain may avoid physical activity and work, and potentially become fearful, depressed or anxious, which can lead to higher risk of disability,” he said. “Unfortunately, sometimes the advice given to people with low back pain can reinforce unhelpful beliefs and responses to pain. This is why the conversations healthcare practitioners have with their patients are paramount to their recovery.

“For a new episode of low back pain, if a patient is not recovering within six weeks, we need to reassess them and consider referral for additional targeted care,” O’Sullivan added.

People experiencing low back pain should seek advice from their healthcare practitioner about the best care for their individual circumstances.

Numbers don't lie

Back problems and back pain are the second most common reason Australians seek care from general practitionersii, and one of the top five presentations to emergency departments.iii iv

People with low back pain also seek help from allied health practitioners, such as physiotherapists and chiropractors. It can cause considerable distress and is a leading cause of disability worldwide. Back pain costs the Australian health system $4.8 billion each yearv, and is the top reason for lost work productivity and early retirement.vi vii

References

i Stanton TR, Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, McAuley JH. After an episode of acute low back pain, recurrence is unpredictable and not as common as previously thought. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Dec 15;33(26):2923-8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818a3167. PMID: 19092626.

ii Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Bayram C, Harrison C, Valenti L, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2015–16. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2016.

iii Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian hospital statistics: Emergency department care 2020–21. Table 4.9: The 20 most common principal diagnoses (3 character level) for emergency department presentations, states and territories, 2020-21 [Spreadsheet]. [Internet] Canberra AIHW; 2022.

iv Edwards J, Hayden J, Asbridge M, Gregoire B, Magee K. Prevalence of low back pain in emergency settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 Apr 4;18(1):143.

v Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria and Deloittes Access Economics. A problem worth solving: The rising cost of musculoskeletal conditions in Australia. In Elsternwick: Arthritis and Osteoporosis. Victoria; 2013.

vi Schofield DJ, Callander EJ, Shrestha RN, et al. Labor force participation and the influence of having back problems on income poverty in Australia. Spine 2012;37:1156–63.

vii Schofield DJ, Shrestha RN, Cunich M, Tanton R, Kelly S, Passey ME, et al. Lost productive life years caused by chronic conditions in Australians aged 45–64 years, 2010–2030. Med J Aust. 2015 Sep 21;203(6):260.e261–6.

19th Victorian Public Healthcare Awards — winners revealed

Recognising leadership and excellence in the provision of publicly funded health care, the...

Dr Vinod Seetharaman appointed Dedalus ANZ Chief Medical Officer

Healthcare technology provider Dedalus Australia and New Zealand (ANZ) has appointed Dr Vinod...

Ramsay Health Care Australia faces charges following patient death

Ramsay Health Care Australia Pty Ltd is facing two charges following the death of a patient at...

![[New Zealand] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89856/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)

![[Australia] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89855/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)