Should naloxone be used to avoid opioid overdoses?

It’s now almost two years since ACT chief minister and minister for health, Katy Gallagher, launched Australia’s first program to distribute naloxone to prevent heroin overdoses. Other states have followed. But is it a good idea?

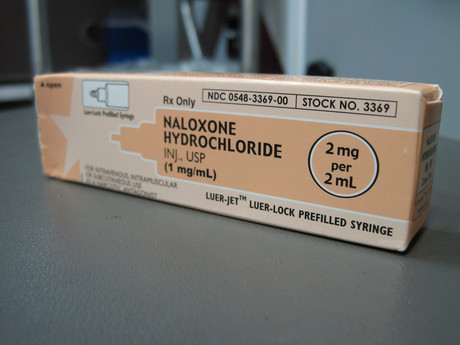

Naloxone is an injectable short-acting drug that blocks heroin and other opioids.

Distributing naloxone to people who inject heroin and other opioids seems likely to help prevent overdose deaths. But existing evidence for its effectiveness and safety is weak.

Overdoses and naloxone use

Overdoses from heroin and other opioids are important for many reasons; every year they involve a distressingly large number of Australians.

About 400 Australians died from a heroin overdose every year in the early years of this century. But heroin and other opioid overdose deaths are now increasing, probably due mainly to prescription opioids.

Most people dying from these overdoses are relatively young. And, non-fatal overdoses have huge mental and physical health costs. There are also often hefty bills for ambulances and admissions to hospital.

Naloxone sounds like a good way to reduce overdose deaths because ambulance and hospital emergency department staff use it successfully to reverse heroin overdoses.

Indeed, many drug users, clinicians, researchers, and government officials strongly support naloxone distribution to drug users, their peers, and families for this very reason.

But I am sceptical. Let me explain why.

The importance of evidence

These days we need to ensure new policy and practice is based on strong evidence of effectiveness, safety and, preferably, cost effectiveness.

Too many past policies and practices were introduced because they “seemed like a good idea at the time”, but later turned out to be ineffective or unsafe. The problem is that, once introduced and found to not work or be harmful, these are often exceedingly difficult to get rid of.

The only evidence for naloxone distribution so far comes from observational studies, which are considered among the weakest form of research design. The abundance of such studies does not compensate for their inherent lack of rigour.

The biological action of the drug and the mechanism of heroin suggests it should be effective for reversing opioid overdoses. But that on its own doesn’t constitute evidence.

Even the fact that naloxone can be used effectively and safely by medical professionals doesn’t tell us whether it would be effective and safe in the very different sorts of conditions likely to prevail when people who inject drugs or their families and friends decide to use it.

The most exacting evaluation of medical interventions are considered to be randomised controlled clinical trials. In a trial like this for naloxone, half the subjects would be given the drug and compared with the other half, who would not. Such a trial is now underway in the United Kingdom where 10% of the subjects have already been recruited.

Some people argue we shouldn’t delay implementing naloxone until the results from this study become available because that will take some time and too many lives may be lost in the meantime.

But that assumes we already know that naloxone distribution is effective and safe.

Plausible alternatives

There are other proven interventions that could also reduce overdose deaths but are being overlooked. Although methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatments reduce overdose deaths by about 80%, for instance, they are difficult to access in many parts of Australia.

And the payment required by patients in some programs makes them ridiculously unaffordable, especially for low-income people.

Providing more of this treatment in prison, especially for inmates close to release, is particularly important as recently released inmates have a very high rate of death from overdose in their first weeks back in the community.

But in most prisons in Australia, it is even harder to enrol in this treatment than in the community.

Rethinking naloxone

Another option is assessing the evidence for naloxone distribution according to the criteria devised by Bradford Hill, a distinguished English epidemiologist.

The nine criteria he devised to appropriately “infer causality from correlational data” are still used today, and are often also applied to evaluate the effectiveness of population health interventions, especially if randomised controlled trials are not possible.

But no one has assessed the evidence for naloxone distribution according to these criteria.

There are several current alternatives to naloxone distribution – expand and improve methadone and buprenorphine treatment (including reducing its cost to the patient), assess the data for naloxone distribution using the Bradford Hill criteria, wait for the results of the UK trial, or undertake an Australian randomised controlled trial.

The number of deaths from an overdose of heroin or other opioids in Australia is unacceptable. We need to make a sensible decision to prevent these deaths, but this decision should be based on evidence rather than just opinion.

Alex Wodak, Emeritus Consultant, St Vincent's Hospital, Darlinghurst

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Perioperative nurses take on surgical escape room

Nursing staff at Calvary Adelaide Hospital have taken part in a new perioperative escape room...

Report: ACN calls for greater nurse UCC program recognition

In the wake of an interim evaluation report of Medicare Urgent Care Clinics, the Australian...

How and why safety and quality standards are evolving

After 30 years in the healthcare sector, Dr Karen Luxford has seen many changes to safety and...