Médecins Sans Frontières Ending TB in Resource Poor Settings

Tuesday, 19 January, 2016

Earlier this year Dr Catherine Berry returned from Uzbekistan where she spent more than a year working as a medical doctor with Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) treating tuberculosis (TB) in the isolated, desert town of Nukus.

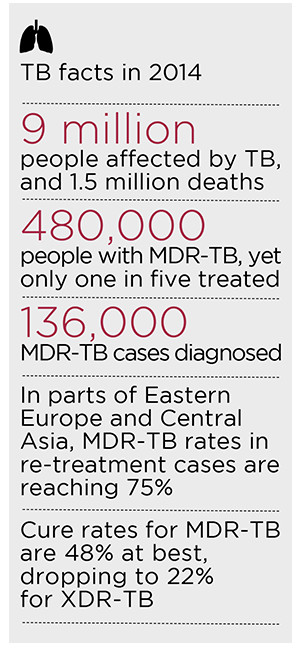

Uzbekistan is one of many countries in Central Asia with high levels of drug-resistant TB (DR-TB), a form of the disease that does not respond to the standard first-line drug regimen.

Like many of the countries Médecins Sans Frontières works in, access to diagnostics and good-quality care, remains limited and the vast majority of people with DR-TB remain undiagnosed and untreated.

Together with the Ministry of Health (MoH), Médecins Sans Frontières implemented a programme diagnosing and treating drug- sensitive TB, and over the years the project has evolved to include children and patients with drug-resistant (DR-TB) forms of the disease.

The idea is that introducing new approaches to diagnosis and treatment of TB – such as ambulatory care, rapid diagnostic tests and a comprehensive patient support programme including education, psychological support, transportation, food packages and financial aid – will help increase adherence to treatment and control the spread of the disease.

TB is a highly stigmatised disease in Uzbekistan, but also there are a lot of misunderstandings about how it is spread. TB is not spread by sharing a cup or shaking hands but this is not always clear. Even patients who are no longer infectious become socially isolated and often have difficulty accessing work and education if their TB becomes known. Patients often don’t want to be seen near healthcare facilities and prefer to have treatment at home. Even seeing the Médecins Sans Frontières car near their house can create gossip. Often patients will seek care outside the formal TB system so as to keep their disease a secret. TB drugs can be obtained from almost any pharmacy and are often taken in adhoc way. These drugs may also be poor quality. Together this may mean patients have a very resistant form of the disease when they finally come to our attention.

Infection control in the field

The prevention of spread of TB requires an integrated approach and needs to incorporate healthcare facilities, communities and households. We want to protect healthcare workers, families, other patients but also the individual patient themselves. The cornerstone of this approach is rapidly identifying drug resistant cases using rapid diagnostic tests such as GeneXpert and getting them onto effective treatment. As soon as patients

are on appropriate treatment they become non-infectious after just a few days.

In Nukus we offer patients community based treatment even for MDR-TB. This allows patients to get support from their community to complete the long treatment which can take up to two years. Hospitalisation is not without risk as patients can get cross- infection with a new and more resistant strain of TB. Family members are at very low risk once they start treatment.

A strong infection control program requires good administrative controls and commitment from high-level management. Otherwise it tends to get deprioritised especially in unstable settings like the ones Médecins Sans Frontières works in. The best infection control measures are often the simplest. Sunlight and keeping clinics, homes and hospitals well ventilated is extremely important and natural ventilation is often far more efficient than the mechanical ventilation such as in the negative pressure rooms we are familiar with. Cohorting drug- resistant and drug-sensitive patients by delivering treatment in different rooms in DOT corners helps prevent cross-infection. We have assisted the MoH of Uzbekistan in making simple renovations to support these important control measures.

A strong infection control program requires good administrative controls and commitment from high-level management. Otherwise it tends to get deprioritised especially in unstable settings like the ones Médecins Sans Frontières works in. The best infection control measures are often the simplest. Sunlight and keeping clinics, homes and hospitals well ventilated is extremely important and natural ventilation is often far more efficient than the mechanical ventilation such as in the negative pressure rooms we are familiar with. Cohorting drug- resistant and drug-sensitive patients by delivering treatment in different rooms in DOT corners helps prevent cross-infection. We have assisted the MoH of Uzbekistan in making simple renovations to support these important control measures.

We try and minimise the time to getting patients on effective treatment. This starts with awareness and case finding. When patients are diagnosed, we try and raise awareness within the family about TB and how it is spread. We try and motivate contacts to come forward for treatment so that they too can get cured. We have also helped support the MoH to get rapid diagnostics like GeneXpert and also full drug susceptibility testing for all patients. This means patients who have MDR-TB can get the right treatment from the beginning and it means that the treatment is likely to work better for them.

We aren’t always able to treat patients in the community and as TB is such a big problem there are dedicated TB doctors and hospitals. We try and promote good ventilation and cohorting in these facilities. Unfortunately, however the temperatures in Uzbekistan vary from -30 to +40 degrees Celsius which means that adequate ventilation is not always possible. We have installed ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) which is electric devices that help to minimise the amount of infective bacteria in the air. This is particularly important in high risk areas like diagnostic wards and in palliative care settings where patients are less likely to be on effective treatment.

We also advise healthcare workers, both our own and MoH, to protect themselves with well-fitting respirators (N95 masks). These are supplied by the Global Fund for TB, HIV and Malaria but we provide support with training of national health workers in correct fitting and usage.

Fighting stigma

A big part of fighting stigma is in curing our patients. Often if the first round of treatment doesn’t work, they become seen as a “chronic case” - incurable and infectious and that further treatment is only for palliation. We try and change these attitudes so that patients can believe that they can get cured and have a normal life.

When patients and families understand the disease properly and that cure is possible, they are more likely to support their family member through the difficult treatment. The family unit in Uzbekistan is very powerful and patients need the support of their family and community to succeed. In embracing this, communities will be protecting themselves. We hope our presence in the region keeps the conversation open and promotes education and understanding.

When patients are diagnosed, we try and raise awareness within the family about TB and how it is spread. It is very important to motivate contacts to come forward for treatment so that they too can get cured. We have also helped support the MoH to get rapid diagnostics like GeneXpert and also full drug susceptibility testing for all patients. This means patients who have MDR-TB can get the right treatment from the beginning and it means that the treatment is likely to work better for them.

When the drugs don’t work

Almost one in four of all new cases of TB in Uzbekistan are multi-drug resistant. MDR-TB treatment is currently only partially effective and we only cure about 65% because the treatment is so hard to take. We have been treating MDR-TB since 2003 so many patients have had lots of treatment before. This means that early diagnosis of MDR-TB and Extremely Drug- Resistant TB (XDR-TB) is all the more important for selecting the right treatment upfront.

In contrast, drug-sensitive TB takes six months to cure and has a 95% success rate. The drugs are also much more tolerable. For MDR-TB and XDR-TB, treatment takes 20-24 months, involve a daily intramuscular injection for the first eight months and can send patients deaf. Other side-effects include nausea and vomiting, hepatitis, renal failure, thyroid disease and suicidal ideation.

Although we invest heavily in infection control in the region, we feel the most important strategy to stop the spread of MDR-TB is to find more effective, shorter and more tolerable treatments. There are now new dedicated TB drugs - bedaquiline and delaminid - available for the first time in 30 years with more to come. Médecins Sans Frontières is involved in operational research and clinical trials to try and find these new strategies but also to get these newer treatments to the patients who need it most.

MSF and TB

Médecins Sans Frontières has been involved in tuberculosis (TB) care for 30 years, often working alongside national health authorities to treat patients in a wide variety of settings, including chronic conflict zones, urban slums, prisons, refugee camps and rural areas. Médecins Sans Frontières’ first programmes to treat multidrug-resistant TB opened in 1999, and the organisation is now one of the largest NGO treatment providers for drug-resistant TB (DR-TB).

In 2014, Médecins Sans Frontières treated 21,500 patients for TB, of which 1,800 were for MDR-TB.

You can read more about Médecins Sans Frontières’ work with TB here: www.msfaccess.org/our-work/tuberculosis

Dr Jennifer Engel

MSF Doctor

MSF Doctor Jennifer Engel shares her experiences working in Treating TB in Mathare, Kenya: “Our clinic is located in the Mathare slum, a poor district of the capital Nairobi. Here we deal with people who have no chance medical care outside MSF. Most of my patients are from neighbouring Somalia and often come here already diagnosed with MDR-TB to finally obtain the necessary treatment.

In Somalia there is no way to get drugs against this particularly difficult to treat form of TB due to the totally destroyed health system. But this means for my patients that they have to leave their home for the time of treatment. And the therapy lasts 20 months! For the first eight months the patients get a daily antibiotic injection. In addition, they need to take about 20 tablets a day. The drugs are often very expensive, although the treatment is free of charge for our patients.

The main difference is that in Mathare, compared to treatment in countries like Australia or Germany, is that we can only treat ambulatory. In the developed world an infectious TB patient always stays in the hospital till they are not infectious (“sputum conversion”). In Mathare we have to educate the patient so they know how to prevent the community and family from getting infected.

Like many countries MSF works in the stigma around TB in Mathare is high. We have patients who are too afraid to tell their family about their diagnosis.

The most important part of infection prevention is the early identification of patients with TB. That means to diagnose and start the treatment as early as possible. With the beginning of the treatment the bacteria load is low and the patient becomes less infectious. Other important measures are good ventilation, cough hygiene (covering your mouth while coughing), separation between infectious TB patients and other patients both inside and outside the hospital, and education of the patients and staff in the hospital.”

Catherine Berry

Infectious Diseases Advisor Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders)

Catherine Berry is an Interim Infectious Diseases Advisor for Médecins Sans Frontières and supports projects in Jordan, Haiti and Nigeria with a particular interest in antibiotic resistance. She recently returned from Uzbekistan where she was working as a research co-ordinator examining shortened regimens for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. Catherine graduated from Newcastle University in 2004 and recently completed a Masters in Public Health and Tropical Medicine. She was awarded NSW Registrar of the year in 2014.

National Allied Health Workforce Strategy: a lasting reprieve?

Hospital + Healthcare speaks with Chief Allied Health Officer Anita Hobson-Powell,...

ADHA accelerates connected care for allied health

After attracting substantial interest from software vendors, the Australian Digital Health Agency...

South Australia gains its first fully rural medical degree

Designed to address the critical shortage of doctors in regional, rural and remote areas,...