Understanding the Value of Philanthropy

Saturday, 13 September, 2014

[hr]Australians are a generous lot who believe in backing health and medical research. But there are some worrying trends emerging in this area of philanthropy. Misperceptions about the proposed Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) are a threat to Australia’s proud history of research firsts, writes Elizabeth Foley [hr]

Scattered through our history are medical research milestones. In 1978, for example, the first prototype bionic ear was implanted. Since then this Australian invention, manufactured by Cochlear Ltd, has provided the gift of hearing to more than 180,000 people world-wide.

None of this would have occurred without some far sighted philanthropy. In the 1960s, when Professor Graeme Clarke was carrying out his pioneering research into the bionic ear, he did not have the backing of the scientific establishment of the day. This lack of support made it difficult for Professor Clarke and his colleagues to secure government or commercial funding. It was donations from private individuals that funded the early work that led to the 1978 prototype. Government backing then eased the path to the industrial development that ultimately changed the lives of many, and created a company that employs 2,700 people and operates in more than 20 countries.

It’s an inspiring story and one we like to tell. It also highlights the absolutely pivotal role played by private donations in medical research. Very early stage, pioneering research is, in many cases, only made possible by private donations. Government and commercial funding fulfil a different brief. Philanthropy is also particularly important in encouraging young scientists to pursue a career in research.

Worryingly though, it appears the absolutely essential function performed by donations is poorly understood, even by those who already back researchers around the country.

A recent Research Australia survey of 1000 Australians found that four in ten who donate regularly to health and medical research will be less likely to do so if the MRFF becomes a reality as currently proposed. Some 18 per cent who donate regularly indicated they would be less likely to donate if government plans go ahead and another 22 per cent said they would be “much less likely”.

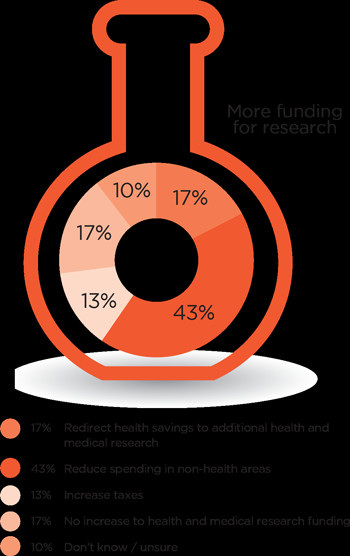

Now we know this intention to dial back is not due to a lack of belief in the cause. The same survey found that 73 per cent support more federal funding for health and medical research and earlier polls have indicated Australians believe health and medical research is the most deserving recipient of donations.

However despite this reservoir of goodwill, it is clear that not enough understand why donations are an essential adjunct to commercial and government research funding, both present and planned.

The country is still coming to terms with the MRFF announced on Budget night in May. Not surprisingly, the concept of the Fund has been received very well, although not universally. There are certainly a number of hurdles still to be jumped. I believe the MRFF is so important to the future health, hope and prosperity of all Australians, and has been received so well by so many that a “funding peace package” must be found.

We at Research Australia are firm supporters of the MRFF. The concept of a $20 billion fund is hugely significant. Budget estimates suggest it should eventually enable an additional $1 billion to be invested in medical research from 2020-2023, which would roughly double the government’s current direct funding in this area.

However it appears that many people do not understand the time lag involved. Current estimates suggest it will take almost a decade until the fund is of such a size that it could back research to the tune of almost $1 billion a year, enough to fund about 40 per cent of all quality research projects currently put forward each year to the National Medical Health and Research Council (NHMRC) in 2013. So all things being equal, even in 10 years time when the MRFF is distributing $1billion dollars, 60 per cent of quality projects will not receive government investment.

However it appears that many people do not understand the time lag involved. Current estimates suggest it will take almost a decade until the fund is of such a size that it could back research to the tune of almost $1 billion a year, enough to fund about 40 per cent of all quality research projects currently put forward each year to the National Medical Health and Research Council (NHMRC) in 2013. So all things being equal, even in 10 years time when the MRFF is distributing $1billion dollars, 60 per cent of quality projects will not receive government investment.

So just how much do we, as a nation, spend on health and medical research? If we use the OECD as a benchmark, it reports that in 2009, our government’s investment in health research and development as a percentage of GDP was below the OECD average, below that of countries like UK, Canada and the USA, and equal to Spain. The MRFF will go a long way to address this shortfall. But as in these countries, philanthropy is still an important element of the funding mix for taking research from discovery all the way through to new treatments, devices, practices and health policies

[pullQuote]“A recent Research Australia survey of 1000 Australians found that four in ten who donate regularly to health and medical research will be less likely to do so if the MRFF becomes a reality as currently proposed”[/pullQuote]

Take the UK for example, the government funded Medical Research Council injected over £766 million in 2012/13, or the equivalent of A$1,385 million into health and medical research. The UK ratio of government funding to GDP is 0.11%, compared to Australia’s 0.09%. Alongside this, the Wellcome Trust invested £463 million (A$837million) into research alone. Fundraising for health and medical research in the UK continues to thrive, despite these two large investments. For example, Cancer Research UK, one of the world’s largest independent cancer research charities raised $887.4 million for cancer research in 2013, up 6 per cent on the previous year.

In the meantime, our research and anecdotal evidence suggests there is very real risk we will lose a significant proportion of the $400 million now donated by individuals each year to health and medical research.

We estimate philanthropy accounts for between five and 10 per cent of the total invested in health and medical research. It is a vital third source of funding alongside private sector investment and government because it goes where government and business don’t like to tread; backing research that is new, high risk, contentious or simply at a very, very early stage. That $400 million that now comes from private donations each year, for example, looms large when compared to the relatively small program of development grants the NHMRC provides to support early proof-of-principle or pre-seed stage research ($14.6 million in 2013).

Interestingly, a number of large gifts to health and medical research have been made in a very public fashion in 2013 and 2014. Examples include Clive Berghofer and Margaret Ainsworth. Another, Paul Ramsay, who passed away a few months ago, bequeathed his multi-billion dollar fortune to the Ramsay Foundation that has made generous donations to medical research, among other causes.

These gifts being made so publicly are hugely important. J B Were, who studies this sector, suggests there may be a cultural shift beginning in the way wealthy Australians give. The publicity generated raises awareness and inspires others to give, much in the way of Bill Gates and Warren Buffett have internationally. Put simply, giving begets giving.

Where we need to continue to build more support for health and medical research is among Mr and Mrs Average. In 2013, a Research Australia survey of 2000 Australians showed 45 per cent of people rated medical research “a most deserving” cause, significantly higher than other causes such as welfare and international aid. Yet of the $4 billion dollars that Australians donate each year, only 10 per cent goes to health and medical research. That’s a far cry from the 45 per cent who rank it the most deserving. That means the sector needs to improve on how it connects with the community at large.

[pullQuote]‘…as our research would have us believe, misconception about the MRFF, a fixation on the $1 billion headline figure that won’t become a reality for almost a decade, and the mistaken belief the MRFF will instantly double the amount of government funding, is threatening to erode that the current base of regular giving.” [/pullQuote]

It’s up to us in the sector to showcase these results and to illustrate how philanthropy is an important third leg in the research funding story.

We have great stories to tell. We can show, for example, how Australian research has helped slash the number of infants tragically lost to SIDS and helped remove the 1950’s myth that asthma was an “overprotective mother’s syndrome”.

And there is still so much to be accomplished. Despite the welcome reductions in smoking rates, this year 11,550 Australians will be diagnosed with lung cancer and survival rates are still poor. It is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer in this country, and is just one of the many worthy areas that need more research.

And there is still so much to be accomplished. Despite the welcome reductions in smoking rates, this year 11,550 Australians will be diagnosed with lung cancer and survival rates are still poor. It is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer in this country, and is just one of the many worthy areas that need more research.

Another growing area of concern is dementia and brain related health issues. This is one of the greatest challenges for this century, with the total worldwide cost of dementia estimated at US$604 billion in 2010.

There is still much to be developed for the MRFF to operate. We regard that as a plus. The Fund is not ready to be spent today. Research Australia is working with its diverse membership to develop a proposal for the government on how this large fund can be dispersed, endeavouring to provide strategic direction on how to most effectively and efficiently deliver the outcome of improving the health of Australians, and also generate economic growth. And it is not as if our nation hasn’t had considerable experience. The NHMRC has been operating for more than 75 years. It presently disperses around $800 million per annum and is considered to be highly effective although, as with everything, capable of ongoing improvement.

Warwick Anderson, CEO of the NHMRC recently commented on the role of the MRFF, ’We envisage that the new funding should be available for such things as the infrastructure around research, registers of diseases, collection of specimens, development of ideas and a degree of commercialisation assistance.’

Private donations will always be needed to ‘de-risk’ projects, creating ‘proof of concept’ that makes the project more likely to gain government and commercial funding. They will also have a role in bridging the gap between the 40 per cent of projects the government will fund in the future and the 60 per cent of quality projects that will miss out. But as our research would have us believe, misconception about the MRFF, a fixation on the $1 billion headline figure that won’t become a reality for almost a decade, and the mistaken belief the MRFF will instantly double the amount of government funding, is threatening to erode that the current base of regular giving.

Indeed, anecdotal evidence from Research Australia’s member organisations suggests donations have already been affected, with regular donors mistakenly believing the additional funding from government was already in place.

This is a huge concern, and further proof that many current donors do not understand the vital role they play.

Another important role for philanthropy is the funding it provides young scientists. In fact, many world leading Australian researchers had their careers boosted at an early stage through philanthropic funding. And this doesn’t have to be large amounts of money. Sometimes it can be support in helping with travel costs to attend an international conference, which is so important for collaboration and idea sharing vital to research.

These are exciting times for all of us involved in health and medical research. We believe a community that better understands that health and medical research can provide better informed support for research endeavours that generate better health outcomes for all Australians.

A community that understands and values health and medical research will be supportive of the increasing public funding of health and medical research and be more likely to make donations to support research. All of us in the healthcare profession can help the community better understand research, and in doing so we will be championing donations to the sector. It is up to us to help foster philanthropy and leverage the goodwill for research that already abounds.

[hr]

Elizabeth Foley

Elizabeth Foley is Managing Director of Research Australia, the national peak advocate for health and medical research. Foley joined this highly influential alliance as CEO in 2011, after 20 years in financial services, where she had enjoyed a very successful career in senior roles in blue chip organisations. Elizabeth is passionate about the role of research in driving improvements in health and the importance of Australian research to building a strong economy. Elizabeth’s strategic intent is to facilitate dynamic debate, shape research policy, encourage government, commercial and philanthropic investment in research and galvanize positive public opinion about research. She has a Bachelors of Business, (marketing) and a Masters of Commerce (finance).

Elizabeth Foley is Managing Director of Research Australia, the national peak advocate for health and medical research. Foley joined this highly influential alliance as CEO in 2011, after 20 years in financial services, where she had enjoyed a very successful career in senior roles in blue chip organisations. Elizabeth is passionate about the role of research in driving improvements in health and the importance of Australian research to building a strong economy. Elizabeth’s strategic intent is to facilitate dynamic debate, shape research policy, encourage government, commercial and philanthropic investment in research and galvanize positive public opinion about research. She has a Bachelors of Business, (marketing) and a Masters of Commerce (finance).

About Research Australia

Research Australia is an alliance of 160 member organisations and supporters advocating for health and medical research in Australia. Independent of government, Research Australia’s activities are funded by its members, donors and supporters including leading research organisations, academic institutions, philanthropy, community special interest groups, peak industry bodies, biotechnology, medical technology and pharmaceutical companies, small businesses and corporate Australia.

For more information go to: researchaustralia.org

National Allied Health Workforce Strategy: a lasting reprieve?

Hospital + Healthcare speaks with Chief Allied Health Officer Anita Hobson-Powell,...

ADHA accelerates connected care for allied health

After attracting substantial interest from software vendors, the Australian Digital Health Agency...

South Australia gains its first fully rural medical degree

Designed to address the critical shortage of doctors in regional, rural and remote areas,...