Wearable Devices In Health

Tuesday, 15 September, 2015

Wearable devices are transforming healthcare and medicine. Christopher Roosen discusses how the design of devices can provide better interaction between patient and clinician.

Just one example is Dartmouth University’s development of an wearables to predict a student’s grades based on their sleeping, studying and exercise habits.

In more formalised hospital settings wearable devices are recording patient location, heartbeat, breathing rate, perspiration, temperature and even the makeup of exhaled gases and waste products.

As the volume of consumer grade health focused wearable devices increases, so does user feedback. Already, early adopters and the leading edge general consumer struggle with the challenges of managing a growing number of experience touch-points.

“Do I need to wear all these devices?”

“When and how often should I check each one?”

“How do I use all this different data?”

“Do I really have to look at all these screens?”

“What information is being captured and why?”

“Why should I bother?”

“How do I get these to connect?”

Macro themes emerge from an analysis of actual and prospective users.

Can users trust the devices they use, or the answers they give? What value does a heavily tracked life give? Do the devices create more workload then they are meant to alleviate? Do the wearable devices create more freedom or constrain it? What are the experiential cost/benefit tradeoffs if Big Brother is always watching our every move, both literally and metaphorically? Will the stress of having constant access to our health data result in even more medical conditions?

User Experience Design provides an interesting perspective on how to intentionally and purposefully design an integrated fabric

of device experiences that provide both value and clarity.

A ‘user experience’ can be defined as the emotional, psychological and physical sum that emerges when someone uses a product or is part of a larger service or system.

Creating a user experience goes far beyond just the visual or graphic design of the screen or user interface of a wearable device. It involves the rich set of features, rules, constraints, behaviour and interactions that make an experience.

More importantly, a holistic experience is not something that happens in a single momentary interaction. Typically we define experience as something that is the combination of many experiences over time and possibly varying locations.

In the case of health and wellbeing, experience extends both up and down the continuum of wellness and across the many interrelated moments that shape our health. From being well and maintaining wellness, through to managing the physical, mental and emotional challenges associated with sickness or end of life.

In the case of health and wellbeing, experience extends both up and down the continuum of wellness and across the many interrelated moments that shape our health. From being well and maintaining wellness, through to managing the physical, mental and emotional challenges associated with sickness or end of life.

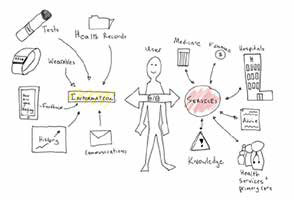

Knowing the complexity of both the real-world journey and of the potential volume and complexity of a web of wearable devices, our focus should not be on designing a single interface, but on creating entire experiences architectures that provide the scaffolding or framework for effective individual wearable devices to fit within a larger holistic system. A well-designed User Experience architecture in the wearable space should be part of a User Experience architecture that puts the user in control and at the centre of their experience.

Potential user experience architectures can be evaluated, measured or analysed according to rules that increase physical, psychological or social wellbeing.

Potential user experience architectures can be evaluated, measured or analysed according to rules that increase physical, psychological or social wellbeing.

[table id=1 /]

Any or all of these rules are not intended to stifle the incredible insight gained when rich sources of data are connected together. As a practical everyday example, imagine a wearable device that could automatically detect every piece of food that a person ate, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Knowing that the aggregate of everyday food choices significantly affects future health and disease, what if the hypothetical device continually predicted and re-predicted your life expectancy based on food choices?Only on the surface does this seem like a good idea. It is more likely that the paranoia and fear associated with ‘losing’ a week off your life after eating one too many desserts would create deeper psychological issues then it would create gains in physical well being.

Instead, user experience rules suggest the system should subtle and slowly nudge the user away from a larger sequence of unhealthy behaviour, rather then giving an abrupt warning. This is more in tune with a trade-off between immediate severe punishment and gentle, long-term guidance.

Granted, there is also political dimension to using a user experience lens on the strategy, analysis and design of wearable devices in healthcare. A user experience focus, by its nature, leads the design of requirements, rules, and technology from the needs, boundaries and goals of individual users or groups. In this way, the wearable device frameworks proposed by user experience can create rapid, democratic and personalised experiences.

"A ‘user experience’ can be defined as the emotional, psychological and physical sum that emerges when someone uses a product or is part of a larger service or system."

However, this can sit in tension with the slower, paternalistic and impersonal experiences of some more formalised healthcare. Though these opportunities don’t need to create opposition, there is a distinct paradigm shift in thinking that occurs when wearables continue to make their presence known in the healthcare space. The goal then remains to create a user experience that balances the best technological capabilities that wearable devices have to offer, with the least amount of political friction to create the best user outcomes.

Christopher Roosen

Christopher Roosen

Christopher Roosen is the owner of Cognitive Ink, a user experience (UX) consultancy based in Sydney, specialising in the innovation and design of products, services and experiences. He has a deep interest in using calm technologies to reconnect people with their communities and the environment. Obsessed with understanding how and why users think and behave, Christopher’s expertise grounded in a Masters degree in Cognitive Psychology and a Postgraduate Certificate in Human Factors (a specialist discipline involving user-focused design to fit the physical and mental capabilities and limitations of human beings).

National Allied Health Workforce Strategy: a lasting reprieve?

Hospital + Healthcare speaks with Chief Allied Health Officer Anita Hobson-Powell,...

ADHA accelerates connected care for allied health

After attracting substantial interest from software vendors, the Australian Digital Health Agency...

South Australia gains its first fully rural medical degree

Designed to address the critical shortage of doctors in regional, rural and remote areas,...