Research reveals likely locations of next pandemic

An international team of human and animal health experts has identified areas at risk of harbouring the conditions that may lead to the next pandemic. The research incorporates environmental, social and economic considerations — including air transit centrality — with results published in the Elsevier journal One Health.

Led by the University of Sydney and with academics spanning the United Kingdom, India and Ethiopia, the open-access paper shows the cities worldwide that are at risk.

The research reveals the locations that could give rise to the next pandemic unless preventative measures are taken — where wildlife–human interfaces intersect with areas of poor human health outcomes and highly globalised cities. Up to 20% of the world’s most connected cities are at greatest risk.

The study methodology builds on understanding sources of pathogen transmission at wildlife–human interfaces by locating the most connected airports adjacent to these interfaces, where infections can quickly spread globally.

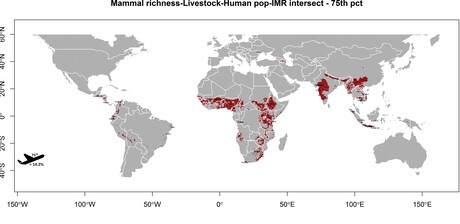

Areas exhibiting a high degree of human pressure on wildlife also had more than 40% of the world’s most connected cities in or adjacent to areas of likely spillover —14 to 20% of the world’s most connected cities at risk of such spillovers are likely to go undetected because of poor health infrastructure (predominantly in South and Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa). As with COVID-19, the impact of such spillovers could be global.

Last month, an IPBES report highlighted the role biodiversity destruction plays in pandemics and provided recommendations. This Sydney-led research pinpoints the geographical areas that require greatest attention.

Lead author Dr Michael Walsh, from the Faculty of Medicine and Health in the University of Sydney’s School of Public Health, co-leads the One Health Node at Sydney’s Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity. He said that much has been done to identify human–animal–environmental hotspots.

“Our new research integrates the wildlife–human interface with human health systems and globalisation to show where spillovers might go unidentified and lead to dissemination worldwide and new pandemics,” Dr Walsh said.

Dr Walsh explained that although low- and middle-income countries had the most cities in zones classified at highest risk for spillover and subsequent onward global dissemination, it should be noted that the high risk in these areas was very much a consequence of diminished health systems. Although not as extensively represented in the zone of highest risk because of better health infrastructure, high-income countries still had many cities represented in the next two tiers of risk because of the extreme pressures the affluent countries exert on wildlife via unsustainable development.

Identifying areas at risk

The researchers took a three-staged approach:

- First, identify where the sharing of space between wildlife and humans is greatest, and therefore where spillover events would be expected to be most common. The researchers refer to this as the ‘yellow’ and ‘orange’ alert zones of two- and three-way interactions between humans, domesticated animals and wildlife.

- Next, identify where areas of high wildlife–human interface coincide with areas of poor health system performance, which would comprise areas expected to miss ongoing chains of transmission following a spillover event (‘red-alert’ zones).

- Identify cities within or adjacent to these areas of spillover risk that are highly connected to the network of global air travel, and therefore may serve as conduits for future pandemics.

“This is the first time this three-staged geography has been identified and mapped, and we want this to be able to inform the development of multi-tiered surveillance of infections in humans and animals to help prevent the next pandemic,” the authors wrote.

Of the cities in the top quartile of network centrality, about 43% were found to be within 50 km of the spillover zones and therefore warrant attention (yellow- and orange-alert zones). A lesser but still significant proportion of these cities were within 50 km of the red-alert zone at 14.2% (for spillover associated with mammal wildlife) and 19.6% (wild bird-associated spillover).

Dr Walsh said although it would be a big job to improve habitat conservation and health systems, as well as surveillance at airports as a last line of defence, the benefit in terms of safeguarding against debilitating pandemics would outweigh the costs.

“Locally directed efforts can apply these results to identify vulnerable points. With this new information, people can develop systems that incorporate human health infrastructure, animal husbandry, wildlife habitat conservation and movement through transportation hubs to prevent the next pandemic,” Dr Walsh said.

“Given the overwhelming risk absorbed by so many of the world’s communities and the concurrent high-risk exposure of so many of our most connected cities, this is something that requires our collective prompt attention.”

High-impact spillover landscapes and cities lists can be accessed here.

Brain and kidney injury treatment after cardiac surgery

A multi-site study to test a treatment that may reduce brain and kidney injury after cardiac...

Domestic violence education: its place in pharmacy

Interviews with pharmacy practitioner educators have identified challenges and opportunities...

Don't Rush to Crush+ — the new digital edition

Australia's essential guide to administering oral medicines safely, Don't Rush to...