Robotic-assisted bronchoscopies could help reduce cancer deaths

A Macquarie University clinical trial of robotic technology that allows doctors to access tiny nodules in the farthest reaches of the lungs is already showing promising results. It could prove to be a game changer in the early detection of our deadliest cancer.

At just 37 and with two children aged five and seven, laboratory technician Cindy Gomez received the chilling news that she had a small growth deep in her right lung.

Gomez’s GP initially suspected she might have had a heart attack due to elevated levels of a protein called creatinine kinase in her blood. While tests found no problems with her heart, they revealed a nodule on her lung.

Some lung nodules have simple causes like infections and do not require radical treatment, but others are the first sign of lung cancer.

“I had never smoked in my life, and the thought that I might have lung cancer was terrifying,” she said.

“Some members of my family smoked, but I had not lived with them for 12 years.

“I only went to the doctor because one of my friends noticed I had lost weight and was looking pale. I am just so thankful that this was discovered early.”

While her nodule was tiny, that did not mean the next steps were straightforward. She was told that because of its size and location, it would be very difficult to take a sample for testing.

Traditionally, the only options in cases like hers have been to remove the nodule without a confirmed diagnosis or wait for it to grow big enough to sample.

Luckily for her and her family, she had the opportunity to take part in a clinical trial at Macquarie University Hospital, where respiratory physicians Professor Alvin Ing, Associate Professor Tajalli Saghaie and Associate Professor Jonathan Williamson are assessing the Noah Medical Galaxy Robotic Bronchoscopy System.

This piece of technology was designed specifically to take biopsies from small, hard‑to-reach nodules like hers — and it may have saved her life.

Diagnosing a silent killer

Lung cancer killed more than 8600 Australians in 2020. It is the world’s leading cause of cancer‑related deaths, though it is only the fifth-most-commonly diagnosed type of cancer.

The main reason for this high mortality rate is that by the time someone with lung cancer begins to notice symptoms, the disease is well advanced and it may already be too late for treatment.

An early diagnosis is the best chance of beating the disease, but in cases like Gomez’s, getting that diagnosis can be challenging, even for the most skilled clinicians.

The new option makes the process much less distressing for those patients who might otherwise have to either wait for the nodule to grow or choose to have surgery that could prove to be unnecessary.

Interventional pulmonologist Professor Ing is chief investigator in the clinical trial.

“Traditionally, biopsies of lung nodules have been performed via a needle through the chest wall and into the lung, but this carries the risk of significant complications, with the possibility that it could cause the lung to collapse or resulting in bleeding that can be very hard to control,” Ing said.

“A standard bronchoscopy is also an option, but in cases where the nodule is very small and deep in the lung, where the airways are narrowest, it can be difficult to reach and hard to accurately sample, so it tends to result in a successful diagnosis in fewer than 70% of cases.

“This new option makes the process much less distressing for those patients who might otherwise have to either wait for the nodule to grow or choose to have surgery that could prove to be unnecessary.”

Mapping the way

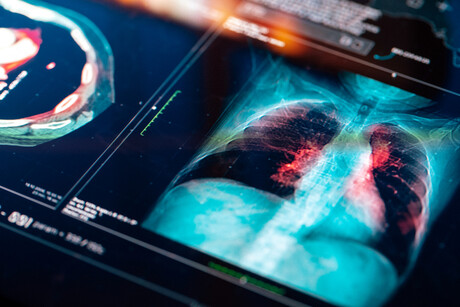

The Galaxy system uses data from CT scans of the patient’s lungs to create a highly detailed GPS‑style map to the nodule.

During the procedure, a probe is inserted into the airway, and with the assistance of the robotic arm, the doctor uses an Xbox-style controller to follow the map straight to the nodule.

Sweeps from a C-arm X-ray machine confirm in real time that the probe is correctly placed, and the robotic arm holds it steady while samples are collected.

So far, 13 procedures out of a planned 30 have been completed as part of the trial, which is being run by the Macquarie University Clinical Trials Unit.

Associate Professor Saghaie has performed eight of the procedures, and said the potential benefits to patients of safer, more accurate sampling methods are tremendous.

“In Ms Gomez’s case, her nodule proved to be cancerous, and receiving that prompt diagnosis with early effective treatment probably saved her life,” he said.

“She has now had the nodule removed, and while she will still need regular monitoring, all of her latest test results indicate she is cancer-free.

“If the nodule had gone undetected, she may only have had a few years.”

It still early days for robotically assisted bronchoscopies, but Ing and Saghaie have achieved a diagnosis for every patient who has undergone the procedure.

And it is bringing benefits not only for people who are found to have cancer, but for those whose nodules have other causes.

Four of the people who have been part of the trial have had non-cancerous conditions that either did not require surgery, or required far less radical intervention than would otherwise have been the case.

A national screening program

Currently, one of the key ways of catching lung cancer early is purely incidental: lung nodules are spotted when people have chest scans for other reasons, as in Gomez’s case.

Countries such as the UK, US, Canada, France and Germany have established routine screening programs to provide regular scans for people at high risk of lung cancer due to their current or past smoking behaviour.

The Australian Government is considering establishing its own national lung cancer screening program, similar to the programs already in place for breast, bowel and cervical cancer.

If such a program were to be established, then far more small nodules would be discovered, and more accurate sampling methods, such as robotically assisted bronchoscopies, would be in high demand.

But robotically assisted bronchoscopy is not the answer in every case, and they should not be performed without proper consideration from a multidisciplinary team.

Macquarie University Hospital’s MQ Health Respiratory and Sleep Clinic established a pulmonary nodule clinic last year, with a team that includes interventional pulmonologists like Ing and Saghaie, who work with cardiothoracic surgeons, radiologists and oncologists.

“Just because you can do a bronchoscopy, that doesn’t mean it’s the most appropriate thing for every patient,” Ing said.

“Some patients will go straight to surgery because the mass in their lung is growing quickly, with other tests suggesting lung cancer, while others will need radiotherapy because they are too frail for general anaesthetic and surgery.

“It’s very important that all the patient’s circumstances are taken into consideration on an individual basis, and this is where the multidisciplinary team approach really comes into its own.”

Republished from Macquarie University's The Lighthouse.

Originally published here.

Six big ideas for beating brain cancer

The University of Newcastle's Mark Hughes Foundation Centre for Brain Cancer Research has...

All metropolitan public hospitals miss out on green light

AMA's hospital logjam finder uses a traffic light system to indicate care within the...

Brain and kidney injury treatment after cardiac surgery

A multi-site study to test a treatment that may reduce brain and kidney injury after cardiac...