The boy with genetically modified skin

A seven-year-old with a lethal genetic skin disease has had a fully functional outer skin layer reconstructed from his own skin cells after they’d been genetically modified to cure the condition, according to European researchers.

Since birth, the disease has caused the child’s skin to become fragile and to blister all over his body, caused by a genetic skin disease called junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB). The scientists grafted the new skin onto the affected areas — 80% of the patient’s body — and, over the next 21 months, the skin adhered to the layer below, coped well with pressure, healed normally and didn’t blister.

JEB is a severe, often lethal, genetic disease that causes the skin to become fragile. Mutations in the genes LAMA3, LAMB3 or LAMC2 affect a protein called laminin-332 — a component of the basement membrane of the epidermis — leading to blistering of the skin and chronic wounds, which impair the patient’s quality of life and can lead to skin cancer.

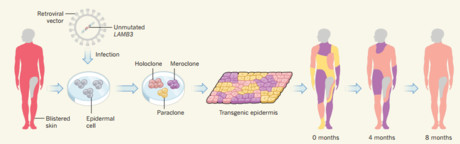

Previously, the treatment of two patients had provided evidence that transplantation of transgenic epidermal cultures — groups of genetically modified epidermal cells — can generate a functional epidermis, leading to correction of JEB skin lesions. However, only a small area of skin was reconstructed.

Using skin cells taken from a non-blistering area of the patient’s body, Michele De Luca and colleagues from the Centre for Regenerative Medicine of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, in Italy were able to reconstruct the epidermis. From the skin cells, the authors established primary keratinocyte cultures, which were genetically modified using a retroviral vector to contain the non-mutated form of the gene LAMB3. Sequential transgenic epidermal grafts were applied on a properly prepared dermal wound bed, so as to cover the patient’s affected body surface.

Over the course of the next 21 months, the regenerated epidermis firmly adhered to the underlying dermis — even after induced mechanical stress — healed normally and did not form blisters.

Through the process of clonal tracing, the authors found that the human epidermis is sustained by a limited number of long-lived stem cells which are able to extensively self-renew and can produce progenitors that replenish terminally differentiated keratinocytes.

The findings are reported in this month’s edition of the journal Nature.

AdPha welcomes "win for all Australians" PBS news

Advanced Pharmacy Australia has welcomed the announcement that over 400,000 Australians each week...

NSW sees ramping reductions across some of its busiest EDs

Some of NSW's busiest emergency departments have seen significant reductions in hospital...

RACGP calls for obesity-management medication PBS subsidy

Following its new position statement on obesity prevention and management, the RACGP is calling...